🤖 + 🍺 Bots and Beer 2x07 - A Short History of Alternate Reality Games

The Bots + Beer newsletter ran for about 3 years between 2017-2020 during a time when I was highly involved in chatbot and artificial intelligence development. It was eventually folded into Codepunk as part of the Codepunk newsletter.

Some portions of this newsletter were contributed by Bill Ahern.

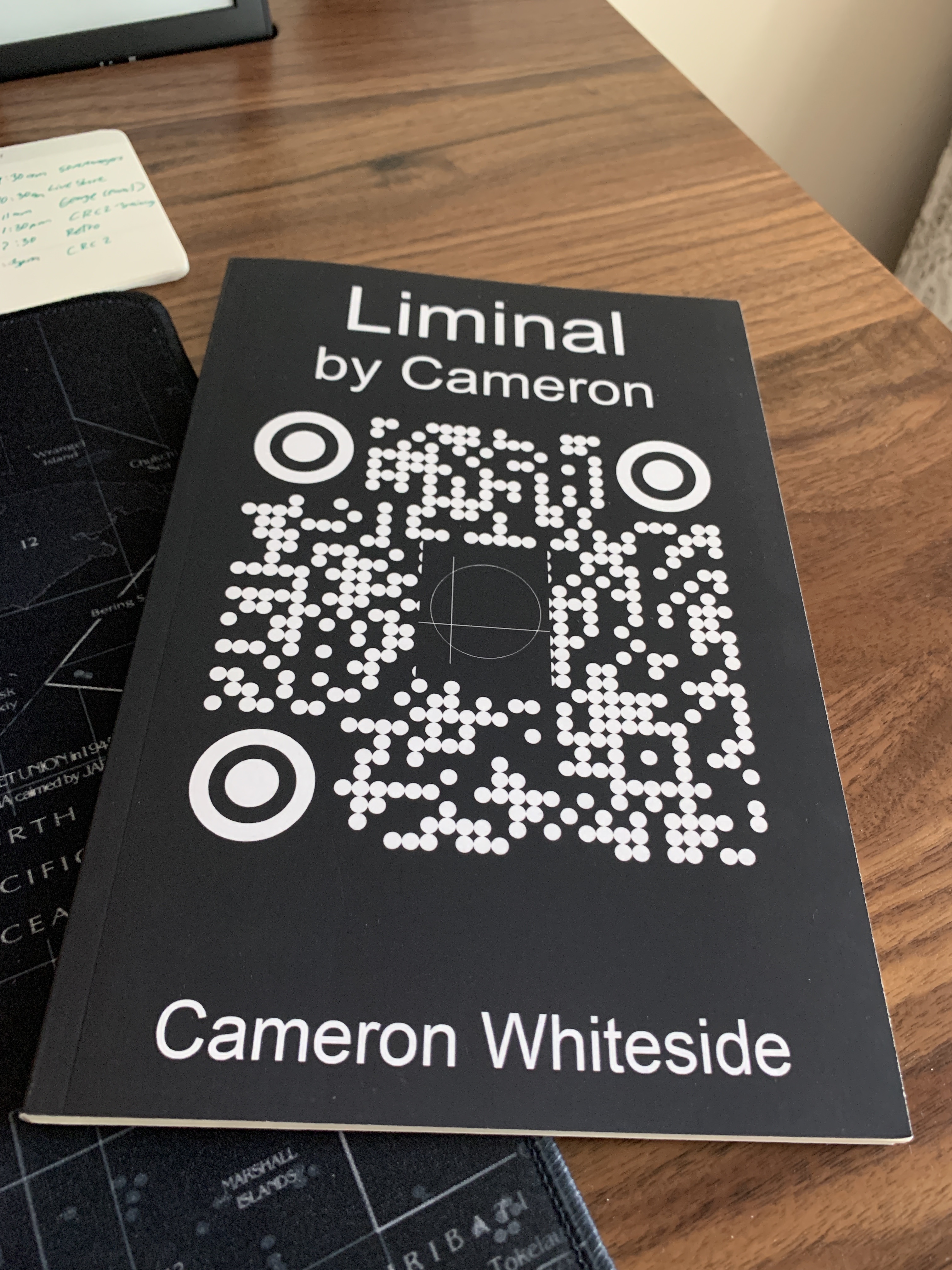

I used to review a decent amount of books on Amazon a few decades back. For a while there, my ranking was pretty high. As a result, I would often get researched and emailed by authors looking to give away a free book for a review. This died down after a while, but every so often I get a random request or a random book in the mail. Like this book, for example:

Just an average day where some random dude sends you a short book with a QR code on the cover. You flip it over and read some of the back matter talking about how the book needed to be "fiction" because it was the only way it could "get out." The back matter concludes about some sort of warning about something that's been unleashed. The book is "written" by Cameron Whiteside. I put written in quotes because check out this bio:

Cameron is a pseudonym used by a plethora of evolutionary intelligence agents throughout the galaxy. Like Monty Cantsin, Luther Blisset or Saint Germain, you never know when or where he's going to pop up. He is rumored to never sleep, moonlight as a technology consultant, daylight as a fireproof vampire, live by the motto: Non Serviam! and almost never fail to leave a ticking bomb behind.

The QR code actually sends you to a web site, where I can't tell if the web master is actually looking for the author or trying to sell his book. It's a *.wtf TLD extension… WTF, indeed.

All of this is a strange combination of intriguing and silly, but that range is completely dependent on the weather and the time of day. Read those same words at night in a rainstorm, and you end up with a different emotion. That's true of all fiction… or non-fiction masquerading as fiction… or fiction masquerading as non-fiction masquerading as fiction… My head hurts.

This reminds me of two things: For one, it reminds me of my good friend James Curcio's Join My Cult which was a fictional book written in the first person where the narrator was writing it from inside an insane asylum trying to drive his doctors crazy. (I read some weird things).

The second thing it reminds me of is an alternate reality game (ARG). ARGs were en vogue for a short period of time, mostly heightened by the Internet and the obsessive attention to detail that fans of Lost had for Easter eggs inside of the television show. The producers of Lost (and marketing agents) went out of their way to create not just internal Easter eggs that fans would seek out on the Internet, but also Summer (off-season) books, games, web sites, and Internet sensationalism to drive the story outside of the boundaries of the television show. Books and web sites were created as if they existed in the real world to flesh out the details of the show, expand the story, and create an interactive way for fans to keep the viral nature of Lost's popularity growing. This was transmedia, but the act of exploration and putting the puzzles together inside of a semi-fictional world constituted the "game."

This wouldn't have been possible without the Internet, and Lost was popular at a time when spoilers were prevalent and Google was dominant. No dark corner of the Internet was unexplored and no Internet stone was left undisturbed as fans tried to decide the overall connectivity of the story in the book that Sawyer was reading to the story that the show was trying to tell (and other red herrings that—looking back—were just red herrings since Damon Lindelof had a hard time smoothing out rough edges to complete stories).

ARGs didn't start with Lost. I'm actually intimately family with an ARG that existed in the early days of the Internet—one that might actually be the very first: Ong's Hat.

Ong's Hat was a story circulating in the early days of connected machines before personal computers were even close to being prevalent. In fact, the Internet was just a nice cross-section of media growth that helped supplement the curiosity over Ong's Hat. The original urban legend was primarily pushed in a way that was reminiscent of the 'zines of the 80's. Photocopied pamphlets left in unsuspecting places. The 'zines and mail order newsletters of the 80's (Bill used to run one called Television Religion) were how the underground delivered information and strange new worlds. When computers came onto the scene, the hippie culture of the 70's—having failed to bring love to a Vietnam War-torn country—transitioned to apotheosis via computer—a movement that evolved into left libertarianism in the least and transhumanism in the most.

Computers were a communication revolution promoted as an information revolution. Douglas Rushkoff surmised that large corporations pushed the idea of an "information revolution" because information could be commoditized and sold. As a communication revolution, the early days of the Internet were filled with bulletin board systems (BBS), Gopher servers, communities like Stewart Brand's The WELL, and one of my favorite underground message boards Barbelith (which came a bit later when the World Wide Web was young).

The evolution of how we communicate on the Internet has had some drawbacks: The speed of communication has made information discovery easier, but minimized the effort of research, and made some people more susceptible to misinformation.

Charting the early days of the Internet—although communication could be instant—platforms weren't uniform. You gathered information on BBS systems, UseNet news groups, web pages, etc. Communication was slower because research was slower and more detailed. You wound your way through the nooks and crannies of the Internet to seek out arcane knowledge. It wasn't handed to you. The side effect of this journey was that it produced more thought-provoking analysis. If someone was sharing something on the Internet, you could be certain they read it. There wasn't some automatic reshare button. It took effort to find and effort to disseminate. Although the Internet was growing as a tool for communication and information, it was still very much "underground." Even as these underground communities grew, the nature of "community" allowed for the prosperity and diversity of many different communities. This produced an authenticity to the work, the research, the discussions, and the "game."

Today is different. Google serves all of our searches. Facebook and Twitter have become the centralized Internet communities. Information is easily sharable and seldom read, leading to clickbait headlines. We speak in memes, gifs, and emojis in order to have a voice inside the noise. This has lead to inauthentic culture, speaking before thinking, and an Internet datastream that allows anti-vaccination material to propagate faster than the scientific take-downs that overturn them. Even someone as anti-consolidation as Rushkoff uses Medium: A platform busy sucking up all the blog posts of burgeoning and professional writers.

In fact, in the context of ARGs, mass corporatism, the Internet, and Facebook advertising are even sucking the life out of sanything remotely looking like a game. It seems like each day my Facebook feed has at least one "we'll mail this killer box to your door so you can investigate a murder" mass produced experience. The real world isn't much different with the proliferation of Escape Rooms. These experiences lack a sufficient subjectivism and are devoid of the authenticity of some of the original ARGs that required a devote amount of creativity, time, and exploration.

Coming back to Ong's Hat, this story—ultimately attributed to writer and technologist Joe Matheny—circulated through BBS and printed pamphlets in a slow-burn, yet satisfying experiment in early transmedia that ultimately was a huge inspiration of the ARGs from a few decades ago. Ong's Hat was an experiment in media, message, and communication, but became an ARG through the persistent research of Internet denizens hungering to understand more. The quasi-conspiracy of the story was wrapped in advanced physics concepts at a time when Chariot of the Gods was resurging in popularity and quantum physics was being seen as a bridge to a new religion. It was also tied tightly to obscure people and places that existed with enough "almost" history that made it believable.

Take this description of the urban legend's location:

Local lore tacks the unusual name to Jacob Ong, a 17th-century settler who, legend has it, angrily threw his hat into a tree after a lover's quarrel. Some Ong-family descendants say the name was once "Ong's Hut," and it was only ever one or two buildings. Henry Charlton Beck, who depicted historical Ong’s Hat as a rowdy, boozy outpost in his 1936 book, Forgotten Towns of Southern New Jersey, later recanted his descriptions, saying he'd fallen for "elaborate traps" set by locals to mislead him about the town's past. Whatever it once was, Ong's Hat has since been completely swallowed by the forest, though the name stubbornly pops up on maps and lives on in the nearby Ong's Hat Road.

Such realness, yet uncertainty, feeds the legends of the New Jersey Pinelands (whose denizens include the Jersey Devil). Locals known as Pineys or Pine-Hawkers have a similar eeriness and mystique as residents of Appalachia. It's a setting that makes for a good horror story—a Lovecraftian mixture of high science and Old God magic. Previously, these stories were legends passed down through families and local lore, but the Internet gave Matheny an opportunity to craft and disseminate a world-building exercise to see how new technology and forms of communication could infect and grow.

Ong's Hat was once home to secret experiments led by the Dobbs Twins, a pair of Princeton scientists who'd been forced to build a secret lab out in the Pine Barrens after their work in "Chaos Studies" got them booted from the academy. Nearby, a mystic scholar and carpet salesman named Wali Fard had established the ragtag Moorish Science Ashram, and over time the scientists and spiritual seekers met and began to merge their pursuits, blending meditation, physics, alchemy, and metaphysical disciplines like remote viewing in never-before-seen ways.

This description came not from a book, not from any Internet articles, but from a masterfully crafted brochure—letting the story grow from the brochure descriptions rather than telling a concise tale. The use of Princeton is reminiscent of Lovecraft's obsession with Miskatonic University (sometimes attributed to Brown University in Lovecraft's own Rhode Island), while the blending of new science with chaos magic comes across as influenced by the B-rate Lovecraft movie adaptations that put forth quantum physics and chaos math as the equivalent of old world magic. This was at a time when the Internet was making the acquisition of obscure works by people like Aleister Crowley and Kenneth Grant easier (although expensive) to find.

But the story was much, much more than just an homage to Lovecraftian-style themes. Matheny blended together real places and events with conspiracies realistic enough to be believed, but ideas and events bizarre enough to be disbelieved, creating a surreal experiment where people reading, researching, or exploring the legend get caught up in their own seemingly pan-dimensional journey. The use of different media formats to further the story was clearly a transmedia art project before transmedia was even a thing that artists were heavily exploring.

Ong's Hat was such a potent Internet legend that eventually it become the subject of thesis research and was published in a college textbook. This textbook associated Ong's Hat with a tradition of legend-tripping:

Dating from centuries before an Internet became available, the "legend trip" is a ritualized quest in which participants explore legends of supernatural events and test their truth by trying to make them come alive in the here and now. How? By rehearsing the rituals by, for example, visiting sites of legends of the supernatural, and engaging there in the incantations, invocations, or other hocus-pocus that will supposedly conjure up some esoteric spirit or force. Legend trips are, then, collective dares-trips to haunted houses, barns, or abandoned asylums, say-that often frighten the daylights out of participants, who usually are teenagers eager for the thrill, and thus prone to credulity.

Ong's Hat always fascinated me as a story. Among many other reasons: The Ong's Hat restaurant (today Apanay's—although I believe it has since closed) is a place I've eaten at quite frequently. Ong's Hat road is less than 100 yards from my best friend's house. I grew up right outside of the Fort Dix/Maguire Air Force Base area in a neighboring town named Browns Mills (45 minute from Philadelphia), and I'm no stranger to the Pinelands. With the demise of Barbelith as an online community, some of us who frequented the web site and read too much Grant Morrison eventually collaborated on our own projects together. It was during this transition that I discovered not just Ong's Hat but it's purveyor Joe Matheny. I became associated with Joe Matheny through James Curcio when a few of use were trying to help James get Mythos Media off the ground. Joe and I emailed back-and-forth on occasion, and—with Joe having experience in the technology industry—we've kept in touch. One time I emailed Joe about why he chose Ong's Hat of all places (it always struck me as such an odd and obscure choice), and he mentioned that poet and philosopher Hakim Bey's family used to have a cabin in the New Jersey Pinelands not far from there.

Even today, the origins of Ong's Hat—although laid out on paper and in academic textbooks—is still vague. Was it based on a previous work? Who were all the players involved and what did they hope to gain from this experiment? The "game" as it is, is at an end, but the legend continues to live on like any good mythology. In many ways, like Slenderman, Ong's Hat is a creation of the Internet that continues to have a "reality" online even if the real world has since understood it's fiction. It's become a golem of words, places, and ideas that continues to trap the curious, and for those that exist and explore the virtual world, it's as real as any historical event for it is an actual piece of Internet history, showing us how the communication of ideas can virally propel the behavior of individuals across distances far greater than any folklore could imagine.

What Ong's Hat shows us is how technology can change and propel narratives regardless of facts. Even as Ong's Hat was shown to be a "story" in the traditional sense, many refused to believe that it wasn't based on true occurrences. When I reflect on our current landscape filled with false memes and post-fact Facebook posts, and I look to a future of artificial intelligence-generated deep fakes, understanding how and why narratives behavior in this way is paramount to understanding how the future of media, disinformation, and politics is going to play out.

The Internet Archive has a collected "CD" of the Incunabula Papers, if you're interested. You can also read a collection of articles and archives at the web site.

Schlafly Sour Gruit

When I picked this beer up (it was a four pack) there was a lot of dust on the top of the bottles, which made me concerned for the freshness as well as the taste. Schlafly generally makes good beer, but this one was designed to look like some old, high society alcohol label. I was skeptical, but am happy to report that appearances are certainly deceiving. The beer poured with zero head, and the taste was sour, but muted by the gin barreling. I hate gin, but it tampered down the sourness with the orange peel adding some bitter notes. It ended up quite balanced, and was a good, late night drinking beer for watching horror movies.

Maybe there's a nice Lovecraftian sci-fi style movie on Tubi or something.

Credits

Header photo of Ong's Hat Road by Michael Szul.