🤖 + 🍺 Bots and Beer 2x10 - Understanding Pace Layers

The Bots + Beer newsletter ran for about 3 years between 2017-2020 during a time when I was highly involved in chatbot and artificial intelligence development. It was eventually folded into Codepunk as part of the Codepunk newsletter.

Some portions of this newsletter were contributed by Bill Ahern.

All the way back in the first issue of this year, I wrote about GitHub's Arctic Code Vault in what would truly be a turning point for this newsletter. That issue marked a future period of consistency focused on a singular thematic approach that we've continued to this day. (Although I did have someone unsubscribe recently saying I was too wordy 🤷♂️)

A few days ago, I logged into my GitHub account and saw a little note (what they're calling badges) under my profile. Hovering over it gave me:

Arctic Code Vault Contributor

Michael Szul contributed code to several repositories in the 2020 GitHub Archive Program: […]

It was about as close to a surreal moment as when I first receive my Microsoft MVP Award. I joked on Twitter that my code would now outlive me, and hadn't yet figured out if that was a good or bad thing yet.

What GitHub is doing is hugely admirable, and there is no financial benefit to them doing this. They recently announced the first deposit of code into the vault after the COVID-19 pandemic delayed trips to the Norway, and the tech press quickly picked it up.

GitHub's archive partner Piql wrote 21TB of repository data onto 186 reels of piqlFilm—a digital photosensitive archival film that can be read by a computer, or a human with a magnifying glass. […] The service originally hoped to be done with the task by February, but it had to wait until it was possible for the Piql team to travel to the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, which only recently re-opened its borders. It also had to drop its plans to send its own team to the Arctic.

Back when I first read about the GitHub Arctic Code Vault, it reminded me of a Stewart Brand project, and behold, as I read further, the Long Now Foundation (which Stewart Brand founded) was a partner in the program. In fact, GitHub was clear on their usage of Brand's concept of "pace layers."

We've adopted a "pace layers" strategy for archiving code, inspired by Long Now founder Steward Brand. This approach is designed to maximize both flexibility and durability by providing a range of storage solutions, from real-time to long-term storage. The Archive Program is partitioned into three tiers: hot, warm, and cold.

GitHub explains that they've divided their archiving strategy up into temperature zones ranging from near real-time backups (such as GitHub's own data center backups) to monthly through yearly backups (such as with the help of the Internet Archive), and finally backups that occur every 5 years or so (the Arctic Code Vault being an example).

But what are pace layers?

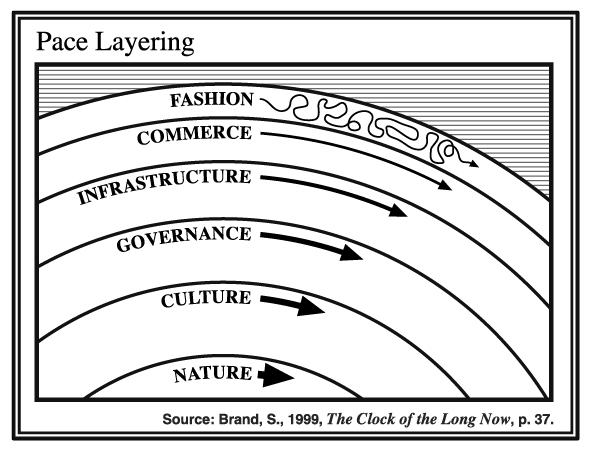

According to Brand and futurist Paul Saffo, pace layers are a framework for thinking about the health of society and how it functions. The idea originated in the Clock of the Long Now book published over two decades ago. The idea centers on different functional layers that work simultaneously, but at different speeds. In his original conception of the framework, Brand gave an example of layers consisting of nature, culture, governance, infrastructure, commerce, and fashion (see the image below).

Pace layers can be considered a rubric of sorts for describing how change occurs over the course of time.

Consider, for example, a coniferous forest. The hierarchy in scale of pine needle, tree crown, patch, stand, whole forest, and biome is also a time hierarchy. The needle changes within a year, the tree crown over several years, the patch over many decades, the stand over a couple of centuries, the forest over a thousand years, and the biome over ten thousand years. The range of what the needle may do is constrained by the tree crown, which is constrained by the patch and stand, which are controlled by the forest, which is controlled by the biome. Nevertheless, innovation percolates throughout the system via evolutionary competition among lineages of individual trees dealing with the stresses of crowding, parasites, predation, and weather.

Brand has previously given other examples in his talks. For example, consider your home, and the rate of change of the construction site, the house, the paint on the outside, the paint on the inside, the furniture, and all of your stuff. Those different components clearly change at different rates.

Pace layers are functionally different from each other and often act in an independent manner, but they are not disconnected from each other. There is an influence between them—a certain interplay.

To Brand, pace layers can act as filters between layers, but the most important aspect of the pace layers are the so-called "slip zones"—where the layers meet. This is where the conflict between layers occurs, and as a result, these layers begin to influence one another, pushing and pulling at their different paces.

Sometimes, this tension between layers becomes too much. Brand terms this "slippage," and the result is a faulty system. To Brand, healthy systems are able to absorb shock from movement at their own pace, but unhealthy systems experience slippage causing layers to damage, and disrupting the system as a whole. Brian Eno posits that those civilizations that have a focused "long now" are more likely to have a flexible infrastructure that can absorb shocks from the tension between layers. We see this in history as culture and governance are always in a dance of change, but if governance cannot keep up with culture shifts, that government can fall, and in its last throws, it can cause significant harm and damage to culture, society, and nature.

This isn't a unique thought by Brand or Eno:

In recent years a few scientists […] have been probing the same issue in ecological systems: how do they manage change, how do they absorb and incorporate shocks? The answer appears to lie in the relationship between components in a system that have different change-rates and different scales of size.

Furthermore, Brand quotes Freeman Dyson in his original paper on the topic:

The destiny of our species is shaped by the imperatives of survival on six distinct time scales. To survive means to compete successfully on all six time scales. But the unit of survival is different at each of the six time scales. On a time scale of years, the unit is the individual. On a time scale of decades, the unit is the family. On a time scale of centuries, the unit is the tribe or nation. On a time scale of millennia, the unit is the culture. On a time scale of tens of millennia, the unit is the species. On a time scale of eons, the unit is the whole web of life on our planet. Every human being is the product of adaptation to the demands of all six time scales. That is why conflicting loyalties are deep in our nature. In order to survive, we have needed to be loyal to ourselves, to our families, to our tribes, to our cultures, to our species, to our planet. If our psychological impulses are complicated, it is because they were shaped by complicated and conflicting demands.

Some elements in society transcend layers, impacting many or all at once. Technology is once such element where&,dash;if we're using Brand's example from the image above—it permeates every area from fashion to commerce to governance and so on. To Brand, technology is like gravity, while other elements like democracy act as catalysts.

The key concept that you can pull out of the theory of pace layers is the observation of speed between the layers. Outer layers are faster, but the layers get progressively slower as you travel towards the inner layers. To Brand: "Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power." Speed, however, is also correlated with quantity, so the outer layers are often more abundant than the inner layers as well. Brand believes that the "paced" variety between layers acts as a stabilizing force for the system as a whole, often preventing destabilizing positive-feedback loops that are looking to crash the system that the layers make up.

The total effect of the pace layers is that they provide a many-leveled corrective, stabilizing feedback throughout the system. It is precisely in the apparent contradictions between the pace layers that civilization finds its surest health.

We have to remember that a "system"—so to speak— is an interconnected set of elements organized in a manner that accomplishes a purpose. The excellent Donella Meadows noted that a system requires three key attributes to exist: elements, interconnectedness, and purpose. With pace layers, the different layers represent the elements involved in the system, while the interconnectedness is where the layers touch and influence one another. Meanwhile, each individual pace layer diagram that represents a system, must attempt to achieve a clear purpose.

We'll cover systems thinking in a future issue of this newsletter.

If we return to GitHub's implementation of pace layers, you can see that each of their elements or layers is a form of archiving that is moving at different speeds:

- GitHub data mirroring and backups

- GitHub Torrent (public event timeline; downloads by hour/day/month)

- GitHub Archive (public event timeline; downloads daily/monthly

- Internet Archive (public repositories crawled, stored, and archived)

- Software Heritage Foundation (public repositories crawled, stored, and archived)

- Bodleian Library (10,000 most starred and most depended on repositories on Piql film)

- Arctic World Archive (Every active repository stored in the arctic yearly on Piql film)

- Project Silica (10,000 year archive on quartz glass in association with Microsoft)

Each of these archiving mechanisms act independently but the technology driving them transcends the layers and allows them to interact with one another by adjusting the technology, speed, and availability of the archiving. Each layer is also created with a different purpose: The inner layers are meant mostly for real-time access and development, while the outer layers are more for disaster recovery, long-term strategy, learning, and civilization preservation. As you move farther and farther to the other layers, the need shifts from the "now" of immediate source control and towards the "long now" of code as history.

Although this might not be as attention-grabbing as a pace layer system about humanity and culture as a whole, this microcosmic look at layering shows us how companies built for the better good can implement this strategy to shift from the regular pace of today's financially extractive economies to a long view of the needs of society, as well as the niche that those individual companies fill.

Throughout writing this, I keep meditating on Brand's key takeaway: Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power. Looking at society today, we have the meme-heavy social media algorithms pushing headlines for biased opinion articles where people don't even read the article or fact-check it; They just read the headlines, agree, and share. We have an economic system that forgets that eco-nomy and eco-logy come from the same root word; The latter being the study of the house and the former being the management of the house—an economy obsessed with quarter-to-quarter growth and upwards financial extraction at all costs. And of course, we have a viral pandemic spreading faster than anyone would have imagined.

My hope is that these are loose, outer layers gathering all the attention for our current "moment," but that the power lies in the long-term thinking that is starting to permeate our society—mainly championed by people of color who are most affected by the inequality, racism, and climate pain brought on by the current trends in our faster layers.

You ever get random tweets of beer? Apparently, I do, and this one comes from Codepunk co-host and Bots + Beer co-contributor Bill Ahern—about to settle down for a night of horror movies and milk stouts (except for the Founders). Those who actually read this far down the newsletter, know how we feel about Founders, which is a staple of any great beer fridge (especially the CBS—Canadian Breakfast Stout). I'm most interested in the mint chocolate chip milk stout on the right—sounds like dessert, and the art on the can reminds me of a good horror movie.

Which horror movie was Bill enjoying? Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter—what looked originally to be the final installment of the Crystal Lake slasher franchise and featured a young Corey Feldman. From a technology perspective, this fourth chapter centered on the idea of masks (pretty important today, huh?), and featured some great scenes of Halloween style masks created by Feldman's onscreen character. As a child of the 80's, seeing this process onscreen was actually a revelation, and there is something aesthetically pleasing about the use and evolution of makeup and artist effects as opposed to CGI. Maybe it's just my nostalgia.

Credits

Header photo of "Layers" by Ian Sane.