A Happy Mutant Reading

This post is a rewrite from the Apotheosis project, and was previously published in both blog and podcast form on Codepunk.

I'm sure you're tired of hearing my opinion on Boing Boing at this point, so you'll be happy to know that this is the post on the subject. We covered both the history and the controversy of Boing Boing in previous posts, so we're going to conclude with some light-hearted happy mutant dialog. And don't worry: It'll be short.

I wasn't sure how I was going to end this arc, but several months ago I started buying a number of 80's/90's books that looked at cyberculture and the early Internet. In addition to some Mondo 2000 gems (we'll get to those in the near future), I picked up a copy of the Happy Mutant Handbook from the crew at Boing Boing. As I began to read through the book I realized that it represented a transition—a true inflection point—where Boing Boing moved from being a source of cyberculture "it" factors to being the affiliate and comedy-driven platform that it is today.

There isn't much doubt that the early Boing Boing zine was a smash success in underground, cyberpunk circles. Codpunk co-host Bill Ahern even ping me on the matter after the last two entries in this Boing Boing arc mentioning how he was a big fan of the early zine work. Boing Boing didn't just assemble the component parts of cyberpunk into a readable digest, but actively contributed and influenced the early culture. In an era where paper was transitioning to electrons, Boing Boing was creating a community through words, influencing much of the computer culture on the West coast—essentially taking over for the Whole Earth Catalog, which was busy trying to transition to the online forum The WELL.

Boing Boing as a zine was both a victim and a beneficiary of early '00 blog culture, and although it continued to thrive with its quirkiness, it lost the edginess that made it prominent with cyberpunk, underground, and hacker cultures.

This downward slide is nowhere more apparent than in the Happy Mutant Handbook—the magnum opus of the Boing Boing side-volution.

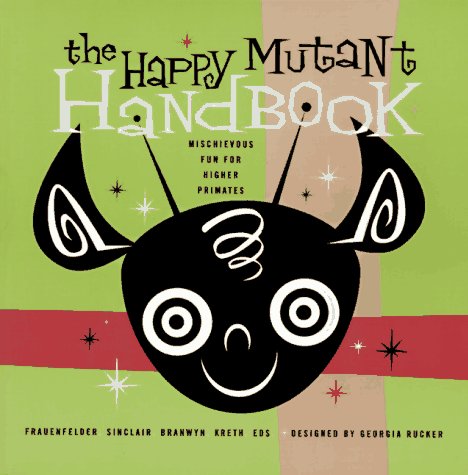

Subtitled Mischievous Fun for Higher Primates the book attempts to take a playful look at Internet culture on the new frontier. From the back matter:

Are you sick of the packaged reality THEY keep trying to sell you? You know: bad TV, hideous magazines, clueless computer technology, and lame attempts at "leisure activities"? It's enough to make you build your own rocket so you can find a solar system that doesn't suck so bad..

The book has its usual suspects of early cyber and counterculture elites, including Bruce Sterling, Rudy Rucker, and R.U. Sirius, but it also includes the usual mix of Boing Boing editorial, including the trademark hyperbole.

If you were expecting a book filled with insider knowledge to hone your skills on the cyber frontier, you'd be sorely disappointed. Beyond the introductory chapter, you'll find chapters on reality hacking, computers, odd cultural figures, toys (of course), and reading material. Happy Mutant might start promising with looks at Burning Man (at a time when it was still an underground movement), hacking, and some quality early Internet guidance, but quickly devolves into a portrait of "cool" gadgets, zines, and other cultural warez—most no longer relevant today, but still a quality part of Internet history.

Still, the Happy Mutant Handbook telegraphs the direction of Boing Boing as a company with a lessening emphasis on the cyberpunk and underground niche elements prominent in the zine to pranks, oddities, and gadgets that would be more likely to drive clicks. In fact, a significant portion of what it means to be a happy mutant is apparently dependent on your effort to prank people judging by the amount of space various pranks take up in the book. Don't get me wrong: I certainly appreciate the articles on the Church of the SubGenius.

Unfortunately, Happy Mutant is less a handbook and is more a collection of blog posts, thoughts, and streams-of-consciousness stapled together by Boing Boing editorial, while being loosely tied to a few name-brand cyberpunks. They even go so far as to profile some of the more famous people in the cyberspace realm as "happy mutants" well after the fact.

In tracing the short history of Boing Boing as a publication, a weblog, and a company, it's clear that they find comfort in being a "Kids in the Hall" version of cyberculture journalism. When you remove a handful of key personalities from their editorial masthead… you're just left with the dust and awkward jokes.