A History of Boing Boing

This post is a rewrite from the Apotheosis project, and was previously published in both blog and podcast form on Codepunk.

We started this series talking about Douglas Rushkoff's Cyberia and mentioning the cyberculture magazine Mondo 2000. It was always the intention to get back to the subjects of that first analysis, but it's impossible to really understand the early years and influence of Mondo 2000 (and eventually Wired Magazine) without discussing Boing Boing.

Boing Boing was a "zine" before it became a web site, and although zines were not exclusive to the counterculture and cyberculture eras, the proliferation of zines reached its apex in the late 80's/early 90's. The Internet made zines easier to distribute by gathering a larger audience through BBS systems, mailing lists, etc., but eventually the evolution of the Internet's publishing capabilities made it easier to publish a web site than a print zine, which pushed a lot of zines out of circulation.

When I say that zines reached their apex in the 80's/90's this, of course, is only as it relates to modern zine production—photocopies from the mouth of Xerox. Zines as a cultural institution have been circulating since the days of the printing press and were a big cause of the original "information revolution" as the printing press allowed the circulation of media outside of the purview of the traditional authorities. Dissident pamphlets provided some of the first instances of what we would consider zines (although from a more serious perspective), and many consider Thomas Payne's Common Sense to be a traditional zine in its own right.

Zines began to proliferate in niche areas thanks to the early science fiction movement post-Great Depression and leading into the mystic 60's. Even Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were in on the zine culture, which was where an earlier version of Superman was first published.

Although the science fiction era was rife with fanzines, it wasn't until Star Trek that a zine began focusing on a media property.

Fanzines were a popular form of communication and collaboration in the pre-Internet days and various media properties were covered from literature to comics to music. The 1970's saw not just a shift in the music scene (from rock and roll to punk rock), but advances in printing technology (and a reduction in cost) resulted in greater growth of the indie zine industry. The continued growth and evolution of zines in the 70's and 80's tapered directly into the birth of Boing Boing.

Much like the retro-computing movement and our recent exploration of modern interpretations of legacy protocols, zines are also experiencing a resurgence in publishing and interest.

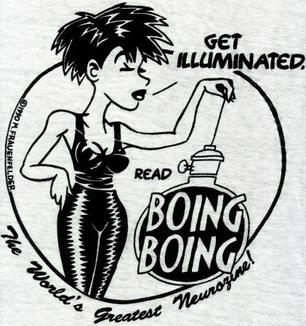

For Boing Boing, life as a zine began in 1988 from the minds of Mark Frauenfelder and Carla Sinclair (Frauenfelder and Sinclair conceptualized the zine a year earlier):

We printed 100 copies on a Xerox machine. I sent a copy to Factsheet Five, which was a zine that reviewed zines. Based on the review that ran in Factsheet Five, we sold all the copies. We also got an order from a newsstand distributor for 100 copies of the next issue. So we printed 200 copies of the second issue, sending 100 to the distributor and 100 to people sending $3 cash to us in the mail. We basically followed a Moore's law style growth curve. The final issue of bOING bOING, number 15, had a print run of 17,500. Unfortunately it was our last print issue because our two major newsstand distributors went bankrupt, owing us tens of thousands of dollars. 1

It published 15 issues before becoming a web-only publication (the web site was launched in 1995).

All 15 issues of Boing Boing are available on the Internet Archive.

One thing that is strikingly different from the zine versus the blog is the obscurity of the content in the original zine. Many people associate early Boing Boing with cyberpunk culture, but Mondo 2000 was always more cyberpunk unless you were an early reader of the zine. The very first issue saw an interview with Robert Anton Wilson to kick off its counterculture credentials. (If RAW isn't enough for you, the second issue leads in with a piece by Anterro Alli) It also contained book reviews of Rudy Rucker's Wetware and Colin Wilson's biography of occultist Aleister Crowley. Sprinkled through the first issue was a number of comic strips covering various counterculture topics, including LSD, while the written content even had some parallels with the hacking and information tutorials in 2600.

As Boing Boing continued to evolve the sharp knife of its zine, you could find references to Discordianism, left libertarianism, mysticism, hacking culture, and just about any mixture of intersectional ideas and alternative thinking that would have Timothy Leary thinking that he'd found the others. Future issues included R.U. Sirius (from the aforementioned Mondo 2000), William Gibson, Kevin Kelly, dark wave music, Tank Girl, David Cronenberg, and other gems of the fringe culture staring out at you from the page of an obscure zine received through the mail.

As the zine grew in popularity, it started to add features and ideas that would become staples of the weblog. In particular Frauenfelder's obsession with reviewing, selling, and distributing what he believed to be "cool things" was a staple. The final issue of Boing Boing more closely resembled the future Happy Mutants book and had a very vinyl/CD case feel to it, while including words by Bruce Sterling.

Frauenfelder (educated as a mechanical engineer) was actually a contributor at Wired prior to the Boing Boing web launch and established enough clout with Boing Boing to catapult himself to additional editorial positions at Wired magazine, Make magazine, and Playboy. Sinclair—wife of Frauenfelder—also established herself as a writer and editor (notably Craft magazine) through the success of Boing Boing.

Frauenfelder's success with Boing Boing also led to a cover art collaboration with Billy Idol for Idol's Cyberpunk album.

The so-called "directory of wonderful things" was partly inspired by Frauenfelder's exploration of the original Blogger software for an Industry Standard article, which caused him to relaunch the Boing Boing web effort around 2000. Whereas the original zine involved media and technology personalities such as David Pescovitz, Gareth Branwyn, Jon Lebkowsky and Paco Nathan—through their quasi-relationship with Wired and various editor hopping—the Boing Boing web site saw contributions by a number notable personalities and spawned the careers of many new ones.

Boing Boing online excelled as a weblog of stream of consciousness posts, links, and other documented "wonderful things" from Frauenfelder. It was one of the original link farms, but because of Frauenfelder's cultural interests, the topics fit a significant growing niche. As a result, the blog found an audience of like-minded individuals looking to explore the early Internet space with the same enthusiasm.

Early Boing Boing resembled very little of the cyberpunk zine that was being published (although it held to some of the themes):

Monday, February 28, 2000

I can't remember how I came across the site for Prospect, a UK magazine with a wide range of articles. Some of my favorites are about Gamma ray bursts (which can wipe out every star systems within a hundred light year radius), and the final diary entry from a guy who has spent the last 13 years in prison for armed robbery.

Sunday, February 27, 2000

I was happy to discover that my friend, Jim Leftwich, has made his neat little macintosh game available. It's based on some characters I created a number of years ago for a comic that came with a Hypercard stack called Beyond Cyberpunk! There's also a Web-version of Beyond Cyberpunk!

Boing Boing did exist before the blogging style that made it popular, but it was as a brief, experimental online version of the zine.

From this initial short-form (micro)blogging, Boing Boing grew in frequency and scope as it carved a niche out of the early Internet with a proliferation of blog posts, as well as an active message board community.

One of the first people to discover the blog was Cory Doctorow, and he would send me lots of ideas of things to write about. After a few months I asked Cory if he would like to have an account on Boing Boing and post directly. He agreed, and I was surprised to see him post seven or eight or more items every day. This was an order of magnitude more than I had been posting. I typically posted two or three items a week!

As a result of Cory's prolific posting, the traffic shot through the roof. Soon after that my friend and a bOING bOING print zine editor, David Pescovitz joined, and shortly after that Xeni Jardin became one of our editors as well. 2

As the weblog developed into a sustainable business, it was eventually incorporated as an LLC: Happy Mutants—the name of which became the title of a future book edited by Frauenfelder. During its most popular era (somewhere around the mid-00's) it was one of the most popular read and cited blogs on the Internet. Topics at Boing Boing were filled by early ideas of Internet technology, gadgets, science fiction ruminations, and left-leaning mutualism and politics.

Boing Boing reached its height during a time when blogs took off as the primary driver of journalism and innovation on the web. In recent years, social media has drastically eaten up web traffic forcing journalists to turn to paid newsletters as a revenue source. Boing Boing experienced its first revenue decline in 2009 after the housing market crisis, and although the site has managed to maintain a significant ranking on the Internet, it has shifted from the darling of cyberculture into mostly a pale imitation of its formerly innovative zine and early blog. Many former readers complain that they can't tell the difference between a post or a paid advertisement.

Oddly enough, they foreshadowed most of this in the last issue of the zine itself:

Well, Boing Boing has come full circle. We've gone from a zine, to a wanna-be-authentic publication, to a stressed out on-the-verge-of-selling-out ad-accepting magazine, all the way back to a small, unorganized zine.3

Comparing the state of Boing Boing today with the original conceptualization of the zine and it seems more like a home for someone to post Amazon affiliate links than a home for cyberpunks.

Although it's too early to tell, after surviving controversy surrounding censorship, Boing Boing now must try to survive without Cory Doctorow and Xeni Jardin—both of whom recently left the publication. Metafilter tagged Doctorow's departure as the equivalent of the Beatles breaking up. That's a bit hyperbolic, but considering how Doctorow's output was a large driver of the original growth of Boing Boing, you can see the correlation.

Despite the ups, downs, and sideways history of Boing Boing, it certainly remains a large part of early Internet culture, and with the modern infatuation with zines, its fun to explore the roots of Boing Boing as a niche cyberculture magazine that brought together a lot of early thinkers. The problem seems to be that as Boing Boing grew as a weblog in the modern era, those original thinkers became few and far between, and the blog was left with Doctorow's activism, Frauenfelder's quirky posts, and a lot of affiliate links—a shell of its former self… and even less so today.