Cyberia Old and New

This post is a rewrite from the Apotheosis project, and was previously published in both blog and podcast form on Codepunk.

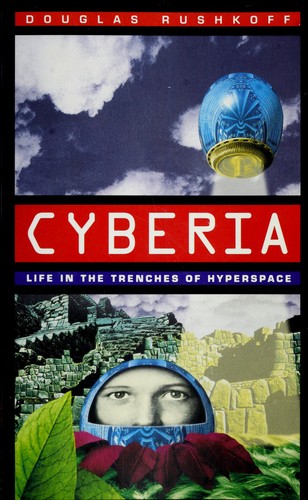

My previous project Codepunk (co-created with Bill Ahern) used the tagline "life in the new cyberia," and although he didn't invent the term, Douglas Rushkoff used the word "cyberia" as the title of the book that really cemented him in early cyberculture. That book? Cyberia: Life in the Trenches of Hyperspace.

Having read the book roughly two decades prior, I recently picked up a used copy of Cyberia. For one, I wanted to see how well the book held up in our modern era, but at the same time, I've become a bit nostalgic for the early years of the Internet and Internet culture in particular.

Every generation—once they reach around 40 years of age—starts to think about how things were when they grew up, and we all come to the same conclusion about how our childhood was better. The music was better when we were younger. The culture was better… The technology—although not the best—seemed more authentic—more visceral. This is, of course, nostalgia—mythology even, and I know that even as I buy up old 80's and 90's books on cyberspace. Some of these books aren't even good, but they feel right.

And yes, I even have a copy of the Mondo 2000 "be a cyberpunk" riff. Mondo 2000, of course, being the cyberculture magazine du jour that predated the commercialization of cyberspace—something, instead, that Wired Magazine did. Mondo 2000 (from the brain of R.U. Sirius) was a West coast indulgence in rave culture, computers, new drugs, and postmodern philosophical exploration—all with plenty of tongue-in-cheek jokes. Despite its short shelf life, it featured people like William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Robert Anton Wilson, and of course Douglas Ruskoff himself.

I do think—with a bit of bias, of course—that nostalgia for early computer culture isn't just nostalgia due to aging out. Computers, technology, the Internet—all of these things were fundamentally different in the earlier years, and as they began to emerge from military and academic usage, many early pioneers saw the transformational value of computation—the authenticity that allowed for maximum exploration, collaboration, and creativity.

I gave a presentation for the Cyberpunk Culture Conference about Max Headroom, and it encompassed the early 80's, MTV, and how the era of Reaganomics reduced the value of authentic culture for the purposes of financial extraction. In fact, I recently took this presentation, expanded it a bit, and put it down on paper—fleshing out the thesis.

Once again, we come back to this idea of authenticity. But is it authenticity or is it just nostalgia?

Douglas Rushkoff began his long journey towards Team Human shortly after college in the San Francisco rave scene where the early mixture of computers, raves, and open culture led to encounters and friendships with the likes of Timothy Leary, Genesis P-Orridge, and Mondo publisher R.U. Sirius, among many others who were prominent in that early scene. Rushkoff even played keyboard in one of P-Orridge's Psychic TV iterations. Cyberia being his first book, Rushkoff began exploring the intersection between emergent culture and media studies, producing books like Media Virus and Coercion that propelled him into the main stream as a media theorist and won him the Marshall McLuhan Award.

From his web site:

Rushkoff's work explores how different technological environments change our relationship to narrative, money, power, and one another. He coined such concepts as “viral media,” “screenagers,” and “social currency,” and has been a leading voice for applying digital media toward social and economic justice.

I was always a big fan of Rushkoff in his early years, and when I ran a counterculture web site called Key 23, I had the opportunity to interview him. In fact, I once participated in one of Rushkoff's university classes where he signed my original (now gone) copy of Cyberia. After reviewing Get Back in the Box on Key 23, Rushkoff sent me an early PDF copy of Life, Inc., which, honestly, as much as he might view the Team Human project as his manifesto, Life, Inc. was really the book that set the stage for everything that came after. It was a detailed history of money, economics, and the evolution of corporatism in America and globally. Life, Inc. explains to us the ailment, and to Rushkoff, Team Human is, perhaps, the treatment—if not the cure.

I certainly have many disagreements with Rushkoff's current Team Human take on technology and culture, but I do believe the podcast is worth a listen and book is worth a read.

I don't think it's just nostalgia that's powering our current yearning for the past. Nobody wants a computer from the 80's. Nobody wants the dial-up speed from the 90's. What people of my generation most often want is the feeling of freedom, yet mutualism, that the early Internet provided. It wasn't a utopia. There were problems. But we accepted the flaws with the machines because it was a new frontier where we all thought we could start over. We could build the democracy inside of cyberspace that was slipping away from us in the real world.

Most of this "slipping away" is the result of regressive taxation, culture wars, financial extraction, and corporatism. Deregulation combined with regressive taxation continues to increase the wealth gap while putting power in the hands of a few corporations: This is the essence of world-building in the cyberpunk genre—runaway mega-corporations.

What we see today when we look fondly back on the past is the difference between the Internet as a collaborative tool of exploration versus the Internet as a venue for serving advertising, collecting private data, and selling "stuff." Those are two completely different Internets in my opinion.

So it is nostalgia. Sure. But it's nostalgia for a better way that many of us feel has been lost. People like Douglas Rushkoff. People like myself and Bill. We want to see that Internet back because what we see right now with the Internet is really just the precursor to all future innovations. If unlimited growth and financial extraction remain the primary goals of corporations and wealthy politicians, the loss of the Internet is just a single niche step and quite small in comparison to what the financial extraction will do to education or the climate. More so than the impact that we've already seen.

And I get that this is a universal, collaborative issue since nothing exists within a vacuum. You cannot disconnect technology from politics. You cannot disconnect technology from climate change. Reagan's 80's birthed consumerism as a primary driving force in America today and in order to increase profits while decreasing costs, we lose originality. We lose authenticity. We sell our souls to the shopping malls and neon lights, but live long enough to tell jokes about it and see it on an episode of Stranger Things.

We're seeing a resurgence in many cyberpunk ideas today. and the nostalgia or the yearn for authenticity—whatever you want to call it—is emerging because those of us who grew up cyberpunk are the writers and managers and storytellers of today. Many of us are in management positions or have founded (and sold) companies. We've reach our collective midlife crises and looked back on what the world has wrought (possibly wrought with a little of our own help), and we no longer find it desirable. We want to progress forward to envision and experience cyberspace as it should have been instead of a mega-corporation's interpretation of cyberspace—filled with trademarks and advertising.

We look at the Internet today and wonder what went wrong. But at the same time, we're the ones most in a position to actually do something about it. First we need to wake up.